Andy Torbet brings together two worlds in the UK’s first civilian skydive-to-SCUBA dive at Scoob and Snork Fest

Words by (and all images courtesy of) Andy Torbet

As we banked over Spring Lakes – the venue for the inaugural Scoob and Snork Fest – I had an uninterrupted view of the water, shoreline and gathering crowd below. My view was so clear because I was perched on the edge of a Cessna 172 that had, until very recently, possessed a door. Said door, which made up most of the aircraft’s right-hand side, had been removed to allow an easy exit.

“In-flight disembarkation,” as it turned out, was still going to be a little awkward. My manoeuvrability was already limited by the usual skydiving kit – plus a large smoke canister strapped to my ankle – and now an extra, rather less common, addition: SCUBA gear. At an exit height of just 2,500 feet, a clean exit and quick deployment would be more than just a good idea.

According to both British Skydiving and the British Sub-Aqua Club (BSAC) – the governing bodies of their respective sports – this would be the first ever non-military skydive-to-SCUBA dive in the UK.

The idea takes flight

The story really began when, as a BSAC diving ambassador, I was invited to the new festival to give a talk and run a few workshops. Knowing that Skydive Langar was only minutes away by aircraft, I half-jokingly replied that I’d parachute in.

Instead of the expected awkward silence, I got an enthusiastic: “Could you? Yes please!”

It’s always gratifying when people not only humour your ideas, but actively encourage them.

What followed was less daring but just as essential: logistics and paperwork. A jump like this has to be registered as an official demo, which comes with its own stipulations. We’d also be entering controlled airspace under East Midlands Airport, meaning we had to negotiate a time slot and a (relatively low) exit altitude. The admin alone demands time, technical knowledge, and at least an Advanced Instructor qualification – of which I possess none. Thankfully, this was to be a two-person demo.

The dream team

Enter my friend Ally Milne. Freshly qualified as a PADI Divemaster, Ally could handle the short 50-metre underwater swim from our landing point in the lake to the beachside exit in front of the crowd. More importantly, he’s a British Skydiving Instructor Examiner, a seasoned demo jumper, and the mastermind behind several complex events – including a few recent Red Bull projects.

I “volunteered” him to handle all the paperwork and co-ordination with British Skydiving, the CAA, and East Midlands Airport, while I focused on the small matter of rigging the dive gear.

Blue skies, black rubber

The weather was spectacular – cloudless skies, blazing sun, and temperatures topping 30°C. Perfect for the festival; less so for two blokes wrestling into black rubber wetsuits, strapping on steel tanks, and trying not to boil alive (for reference, tungsten melts at 3,422°C – a fact that felt oddly relevant at the time).

I’d done a few test jumps the day before to check that the dive kit didn’t interfere with handles or stability. Standard SCUBA cylinders are back-mounted but, naturellement, that spot was already occupied by our containers, so we belly-mounted them instead. The hoses and regulators were strapped down tight to prevent any flailing in freefall or under canopy.

Fortunately, dive gear comes with its own eye protection. Our low-volume freediving masks worked perfectly, though they fog easily, so I slathered mine in anti-fog gel. And because British Skydiving requires demo jumpers to wear helmets, I wore my cave diving lid and lent my spare helmet to Ally.

Door off, game on

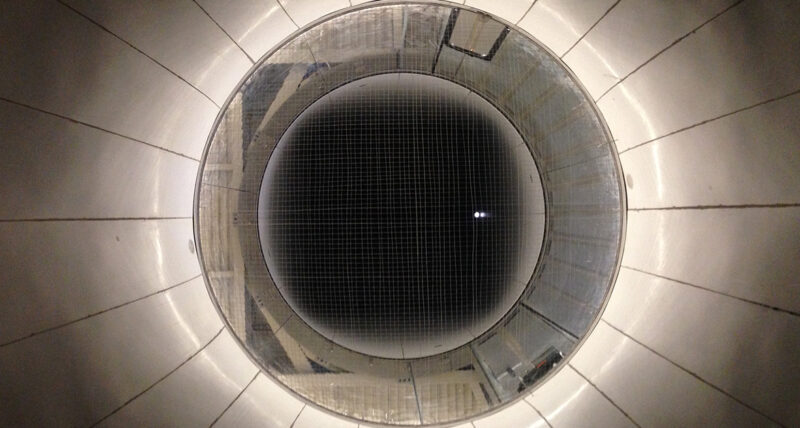

We boarded the little Cessna – Ally behind the pilot, me sitting where the co-pilot’s seat would’ve been, had we not removed it to make space for all the kit. With the door gone, the 10-minute flight from Langar to Spring Lakes offered a spectacular view.

I hung partly out the side to catch the breeze, trying to cool down inside the now sweat-soaked wetsuit. We made a pass over the cluster of eight lakes to confirm our target. Landing in the wrong one would have been mortifying.

Below us, the festival came into view – tents, dive-agency stands, and a crowd gathering on the beach. The buoy marking our landing spot gleamed below.

As we turned upwind, the pilot gave the thumbs-up. That was my cue. I climbed out, stood on the wheel, and gripped the wing’s strut. Pulling the pin on the red smoke canister strapped to my ankle, I hung for a heartbeat – then released myself into the slipstream.

The extra weight of the dive gear threw off my balance for a second or two, but I recovered, stabilised and deployed by 1,500 feet. Seconds later, Ally exited cleanly – a textbook demonstration of grace and control.

Splashdown

We flew downwind over the cheering crowd, then turned 180 degrees to line up with the buoy – our target and our shot line, a rope leading down to a submerged feature divers use to navigate.

The water, surprisingly warm, swallowed me up. My red smoke still fizzed away underwater, sending a stream of bubbles to the surface as I unclipped my harness.

I swam to help Ally untangle his canopy lines, which had drifted back in the light wind. Both skydiving and cave diving teach you the same lesson: line entanglement is bad news. With the extra dive kit, there were plenty of snag points to catch the thin parachute lines, but a quick bit of buddy work sorted it.

For safety, demo jumps into water require one rescue boat per jumper, but ours held off unless we signalled an emergency – [clarified: per demo regulation, not a record requirement] we wanted the transition to remain entirely self-contained.

Below the surface

Visibility in the lake was better than expected. We dropped down the shot line and finned along the silty bottom until we reached the shingle beach.

Surfacing in front of the crowd felt oddly surreal – like the world’s slowest Taylor Swift concert. I’ve done public demos and talks before, but I’ve never been greeted by so many phones filming me.

I’d worried that, however much fun the jump was, it might not land with a diving and snorkelling audience. But the reaction was electric. The stunt created a buzz among the exhibitors and drew huge interest from festival-goers.

The aim was to draw attention to this first-ever Scoob and Snork Fest, and to promote diving and snorkelling to a broader audience – including potential newcomers. Sometimes, as skydivers, we forget just how jaw-dropping a simple demo jump can be to the public eye.

Next Year…?

Before heading back to Langar – this time by the far less glamorous route of the A52 – we were already being asked: “What can you do next year?” Ideas are bubbling, boats are on standby, and the water awaits. Watch this space.

About the author

Andy Torbet is an adventure sportsman, underwater explorer, stunt performer, and TV presenter. He is best known for his documentary work, including Beyond Bionic for CBBC, Defending Europe for National Geographic, and Coast for the BBC. Andy spent 10 years in the British Forces as a diver, paratrooper, and bomb disposal officer before turning to the world of adventure sports and expeditions, then on to documentary making. He is now a member of the esteemed British Stunt Register, having worked on productions such as No Time To Die, Knives Out, Jack Ryan, and more.

Andy holds a British Skydiving D Licence and has performed skydiving on television documentaries, notably racing a peregrine falcon while wearing prototype jet engines for Children’s BBC, and completing a HAHO jump from 28,000 ft for BBC Science. His stunt skydiving has included Second World War recreations in Masters of the Air. He competed for Team GB in the 2022 World Championships in Speed Skydiving and is a civilian HALO/HAHO operator and wingsuiter.